Agonizing over a request for “a high resolution picture of you” (of me), I found myself wondering: when did the image of the individualist artist emerge?

Following this curiosity, I looked at significant artworks through history, testing how quickly and accurately I could identify the artist, style or subject matter that defined major eras in art history.

What emerged was one of history’s most recognizable faces: an old man with long flowing hair and beard, an intense gaze under furrowed brows. This image – a self-portrait drawn in 1512 using red chalk on paper – has become the iconic face of Leonardo Da Vinci. While some scholars question whether it is actually him, Da Vinci gave us this compelling image that made him recognizable centuries later.

“Painting is a mental thing.”

Leonardo da Vinci

Before the 15th century, artists were craftsmen, and art was often created anonymously. The idea of the artist as a unique thinker, the artist-genius, emerged during the Renaissance, and creative intellectuals like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo gained fame. Painted portraits allowed us to shape their image today. However, the most iconic portrait from the Renaissance remains Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, with her ambiguous expression that has intrigued viewers for centuries. More than just a portrait, it became a reflection of the artist’s inner world.

This image of the artist driven by inner vision deepened during Romanticism, and the individualist artist was cemented. Romanticism advocated for emotion and individuality, and art became a form of self-expression. Artists like Delacroix and Goya, even though from different countries, embodied this idea in style and subject matter. Both artists saw art as a way to expose the horrors of war and human cruelty.

“What moves men of genius, or rather what inspires their work, is not new ideas, but their obsession with the idea that what has already been said is still not enough.”

Eugène Delacroix

Delacroix painted his self-portraits with a dramatic, Romantic air, an intense gaze, dressed in dark clothing. His painting Liberty Leading the People, featuring a powerful female figure, embodied emotion, revolution, and the power of the individual in history. It gained popular currency, appearing with Delacroix’s own portrait on the 100 French franc bill (1979-1995), turning the artist and artwork into national symbols.

Responding to the trauma of modern warfare and disillusionment, a new movement, Surrealism, came and sought to unlock the subconscious mind. Frida Kahlo and Salvador Dalí were both connected to Surrealism, but with very different approaches. One painted their reality, the other their dreams.

“I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.”

Frida Kahlo

Kahlo made her pain, politics, and identity part of her portraits – where the artist is the artwork. At times, her face filled the entire canvas, making her self-portraits deeply personal.

“I am not strange. I am just not normal.”

Salvador Dali

In contrast, Dalí cultivated a surreal world where dreams and fantasies turned into artworks. More than just a Surrealist, he was one of the most iconic and eccentric artists of the 20th century. With his cape, cane, and signature twisted mustache, Dalí created a distinctive public persona— recognizing him remains unmistakable. A master of imagination and symbolism, he invites viewers into a reality shaped by dreams.

It was after the 20th century that the artist became a celebrity figure – think Warhol or Banksy.

“The world’s most honest art form is street art. There is no elitism or hype; it is exhibited on the streets for free. It’s the voice of people who aren’t listened to.”

Banksy

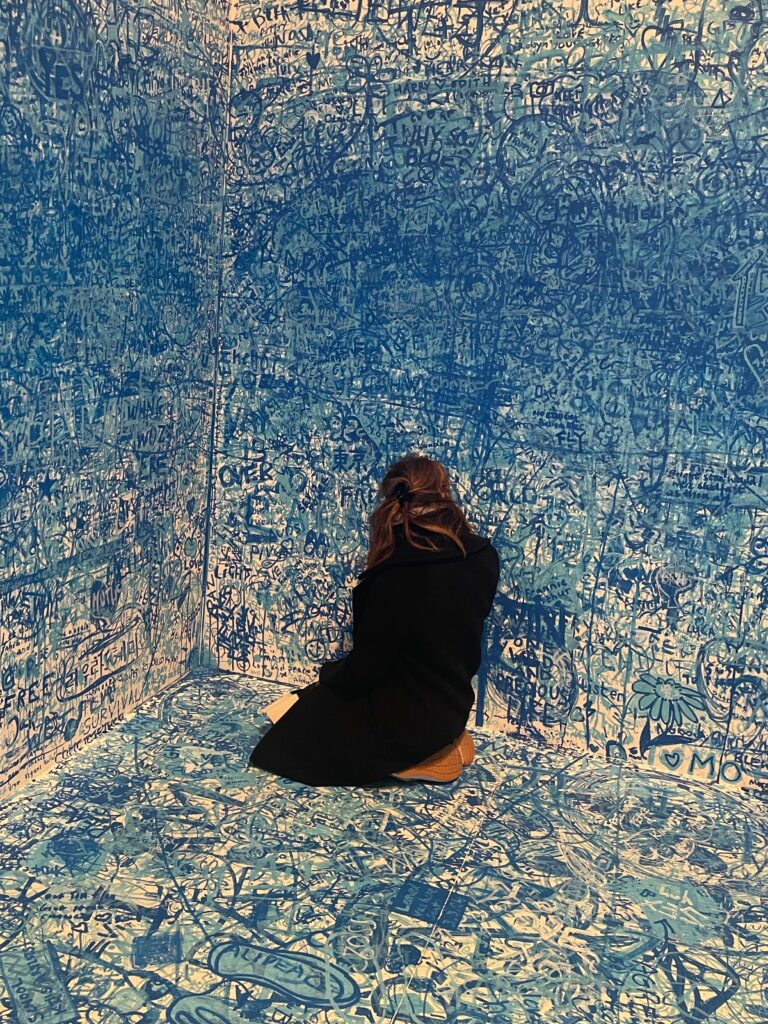

Remaining anonymous to keep focus on his message, not his personality, Banksy’s style is highly recognizable. A brand, not a face – a Banksy is a spray-painted stencil featuring recurring subjects, and an anti-war, anti-authority message. His identity is built on his invisibility and his art’s visibility, using public spaces to let his art speak loudly.

“Art is what you can get away with.”

Andy Warhol

While Banksy chose anonymity, Andy Warhol did the opposite; he made himself a public figure: the sunglasses, the silver hair, the cool persona; all part of the Warhol brand. Yet both artists share similarities in how they reshaped the role of the artist and used their fame to control public attention.

“I don’t think that my art is cynical. I think that it looks at things very carefully.”

Lichtenstein

A Lichtenstein painting is just as instantly recognizable: blown-up, cropped comic strips, Ben Day dots in bright primary colours outlined in solid black. Yet Roy Lichtenstein himself did not become a cultural icon. His style became the brand, not his personality.

Now that we’ve looked at how different artists approach the relationship between their art and public persona, I ask again—how much of the artist should be seen?

“The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.”

Roland Barthes

Barthes argues that the identity of the author (which here applies to the artist) should not control how a work is interpreted. Once a piece of work is created, it’s detached from the artist and made by the viewer.

My conclusion: look not into an artist’s eyes, but through them.

“The canvas listens before it speaks, and when you look closely, it whispers the artist’s name.”

Loulou Bissat

Stay Connected:

https://www.instagram.com/_lframe

https://www.instagram.com/executivewomen_

https://www.facebook.com/ExecutiveWomen

Read more articles: https://executive-women.global/en/beirut-28-july-2025/